The Evolution and Challenges of the US Department of Education

When my sister was little, she had a nightly ritual: Someone had to help her hunt the alligators hiding under her bed before she could sleep. Never mind that we lived in the Midwest, and the closest alligators were at the zoo—safely behind trenches and reinforced glass. The fear was real to her. My dad, patient as ever, would grab a flashlight, stomp around the room, and pretend to wrestle a few before declaring the coast clear. Only then would she drift peacefully off to sleep.

I think about that a lot these days when I hear people talk about the US Department of Education. To some, it is the monster under the bed—a federal agency lurking in our schools, supposedly brainwashing kids, forcing ideologies, and undermining parental rights. However, just like the imaginary alligators in my sister’s room, the threat people claim the DOE poses is more imagined than real.

“The DOE isn’t the alligator under the bed—it’s the flashlight.”

-Levlyn Emet Quill

“The federal government has no business [INSERT AREA OF LIFE HERE]”—it is a familiar talking point, and to be fair, I do not always disagree. There are parts of my life where I would love for the government to see their way out, please and thank you. However, even the staunchest critics of federal overreach tend to agree that some level of governance is necessary, especially regarding the well-being of children and the strength of our democratic institutions. This necessity is particularly evident in the case of public education, which, however flawed, is still widely accepted as a cornerstone of American society. The role of the US Department of Education in this context is crucial, providing a framework for educational standards and practices that ensure a quality education for all.

Yet, from its inception, the US Department of Education has been a political lightning rod. So what exactly does it do? Why was it created? Why do some people want to abolish it altogether? Moreover, is this really about governance—or is something else going on? Understanding the historical context of the DOE’s creation and evolution is crucial to grasping its current role and the controversies that surround it.

I was born just a few weeks into the Carter administration. As a direct result, the only education world I have known was one where the DOE existed. It was there for my life as a student and educator. So, when people feel inclined to list how the DOE is ruining education, I struggle to understand the concerns. The DOE has been a constant presence in my educational journey, shaping my experiences and perspectives.

As a preservice teacher, one of my first required courses was on the history and philosophy of American education. While it was interesting, and there were pieces that I grabbed onto, I was much more concerned at the time with the art and science of teaching than the politics of it. Little did I realize how, as an educator, my existence would be steeped in the soup of American ideas, ideals, and controversies that I had so conveniently tuned out. With all of the current debate over what the DOE is, what it does, and whether it is something we should abolish or fight to save, I find myself wishing I could take a spin in the “Way Back Machine” to try to conceptualize better how we got to where we are today.

So buckle up! That is precisely what we are about to do. Let us explore how the US Department of Education has played a pivotal role in shaping national educational policies. While we appreciate its impact, let’s also seek to understand why it has been marked by debates over its necessity and effectiveness since its inception. Together, we will explore what the DOE does (and does not do), why it has been controversial since its creation, how the US compares globally, and what role the DOE plays in addressing educational disparities.

Life Before the DOE

My first big question about the DOE is: What was the educational landscape in this country like before the DOE? To answer that question, we have to go back to 1867, when the United States was in the Reconstructionist Era after the Civil War. So, yes, it came down to the question of separation of powers, what the federal government’s purview should be, and what should be up to the states to determine. (And also race. Yep, that pesky DEI).

During Reconstruction, debates swirled around issues like states’ rights vs. federal mandates, particularly concerning citizenship, voting rights for formerly enslaved people, and the funding of public education. Southern states, in particular, resisted federal attempts to establish systems of universal education, often seeing them as tied to “Northern interference.” Some of the earliest education debates focused on whether the federal government should fund schools for newly freed Black Americans or whether that responsibility belonged solely to states—a tension that would echo through every era of education reform to come.

“Some of the earliest education debates weren’t about standards or testing—they were about whether Black Americans deserved schools at all.”

Before federal involvement, education in the United States was primarily managed by state and local entities, leading to a fragmented system with significant disparities. The absence of a centralized authority meant that educational quality and access varied widely across regions. In 1868, then-Commissioner Henry Barnard reported: “In some states, whole counties are without public schools or educational organization of any kind” (Barnard, 1868). This quote highlights the wildly uneven access to schooling in the post-Civil War era and underscores the urgent need for federal data collection to understand—and ultimately improve—educational equity.

This need for a cohesive approach to education set the stage for creating a federal entity dedicated to overseeing and enhancing educational standards. The desire to unify the nation and set a high bar for educational standards was short-lived and took a back seat to other issues of the day. Congress established the first Department of Education to collect data and promote effective educational practices nationwide in 1867 (US Department of Education, n.d.). The thought was that if we had a centralized agency compiling data in schools and teaching, we could use that data to standardize and improve education across all states. However, a year later, Congress downgraded the DOE to the Office of Education within the Department of the Interior (History.com, 2024).

Standardize & Improve

Let’s talk briefly about the fears around the word “standardization.” I will admit I am uncomfortable with this word myself. I am uncomfortable with “standardization” because I sometimes fear it could mean my square-peg neurodivergent being forced into a round hole. I am uncomfortable with standardization as a concept because the side of me that geeks out on a super high level about a special interest does not want to feel condescended to by having to waste time proving I can do something rudimentary when I am in the middle of doing something much more advanced and sophisticated. I am uncomfortable with standardization in a way similar to how I am uncomfortable with SMART goals—the idea of being measurable and attainable and the need to hit the goals, not fall short without being judged—I fear this could lead to setting the bar lower than needed.

As I candidly write out my fears, I notice people believe there is only so much quality education to be had. Everyone is afraid of missing out. No one wants their kid to come in last. Those at the bottom have nowhere to go but up, but those at the top fear opportunity will be taken away. I cannot help but think much of the resistance to federal involvement in education is shaped by zero-sum thinking—the belief that gains for one group must come at a loss for another.

In her book The Sum of Us, Heather McGhee (2021) argues that this mindset has repeatedly undermined collective progress in American policy, especially regarding public goods like education. She says, “We have been trained to see each other as competitors for scarce resources rather than collaborators for shared abundance” (McGhee, 2021, p. 7). Fairness is not a limited resource; yet, federal education efforts, including those related to civil rights and equity, often become targets not because they fail to serve students.

Heather McGhee (2021) tells story after story of communities that literally chose to go without—draining public swimming pools, closing entire parks, defunding schools—just to avoid sharing with people who didn’t look like them. It’s gutting to realize how often racism led to the collective sacrifice of something good, just so others couldn’t benefit too. And the worst part? These weren’t isolated incidents. They were patterns—reflections of a deep-rooted fear that if someone else gained something, you’d lose something.

So maybe it’s not all that surprising that right after the Civil War, when the Department of Education was first created, it didn’t take long for it to come under attack. Sure, people said it was about states’ rights or federal overreach—but a big part of the backlash was about who they thought would benefit. According to History.com (2024), “The department, established in 1867, faced opposition from congressmen who associated it with education for the formerly enslaved.” Just the idea that Black Americans might receive a formal education—with federal support—was threatening enough for lawmakers to dismantle the whole thing. The DOE was downgraded a year later. Not because education didn’t matter, but because fairness felt threatening. Because access for someone else was framed as a loss.

And the echoes of that same fear still show up today—sometimes disguised as budget concerns, sometimes as curriculum debates, and sometimes as all-out attacks on public institutions.

So while the Department of Education did not exist, the Office of Education quietly worked behind the scenes for over a century, collecting data, producing research, and offering guidance to states on curriculum trends, school design, and rural education. It did not have the power to tell schools what to do, but it helped paint a national picture of what education looked like across the country. As the nation changed, so did the Office’s home base—first moving to the Federal Security Agency in 1939, then to the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) in 1953. These shifts reflected a growing recognition that education was intertwined with public health and social progress. Over time, the Office took on a more significant role in administering federal programs like the GI Bill, the National Defense Education Act, and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

By the late 1970s, with so many responsibilities and growing public concern about the quality of schools, it became clear that education needed a seat at the Cabinet table once again. So, in October 1979, Congress passed the Department of Education Organization Act (Public Law 96-88) and re-established the Department of Education as a Cabinet-level agency. The DOE, as we know it today, began its work on May 4, 1980. (May the Fourth be with you. Honestly, teachers could use a Jedi moment about now.)

What Does the DOE Do?

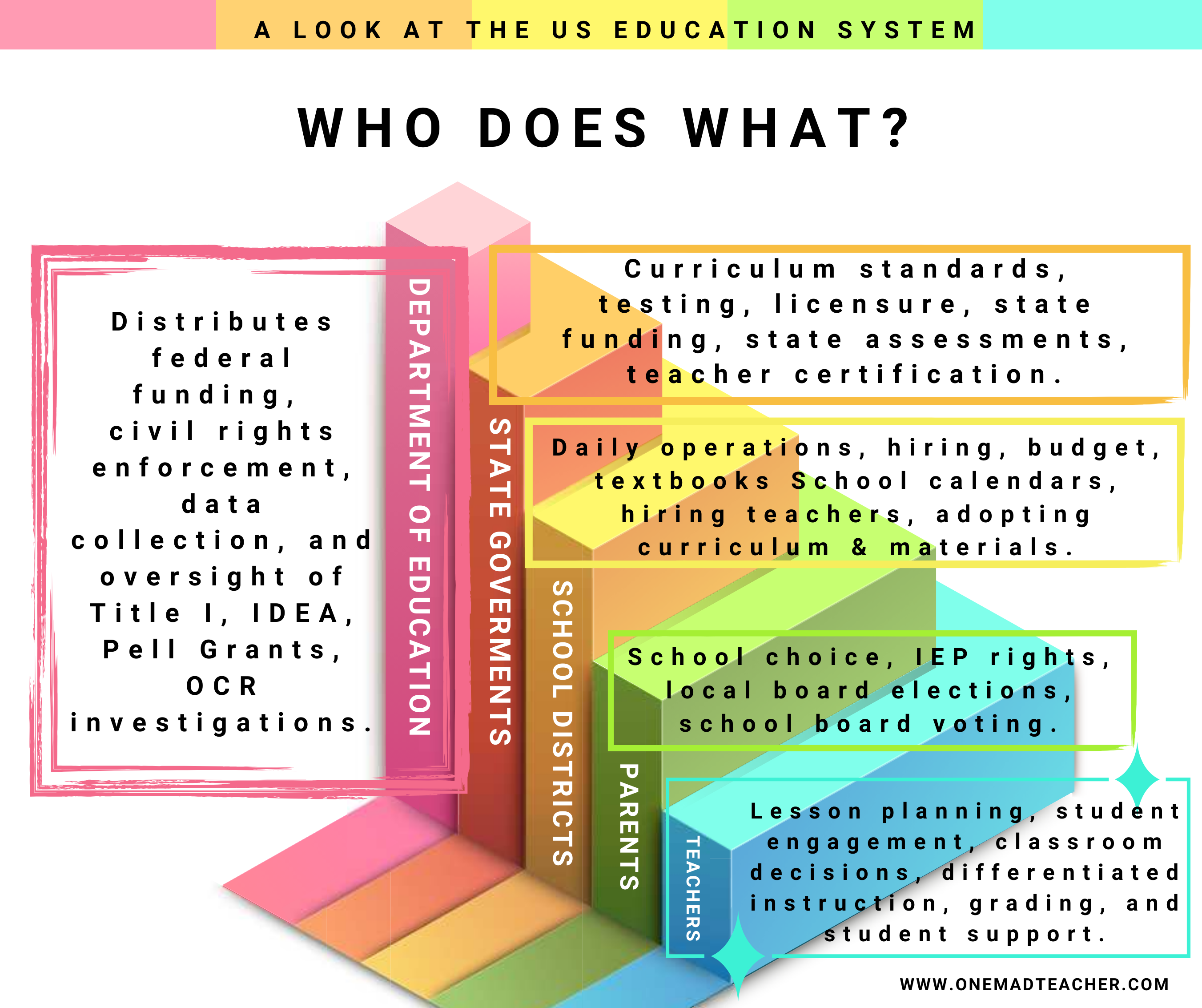

The DOE does not run schools, dictate curriculum, or license teachers. Its real power lies in funding, civil rights enforcement, and accountability. It helps distribute funding to states and school districts based on federal formulas that target support exactly where needed. They also assure accountability— tax dollars are not being misused or reappropriated for some unintended purpose. They enforce Civil Rights and oversee special education under IDEA.

The tides in this country do change, and what is considered Republican in one era is not in the next. The DOE may have started as an idea of the Republicans of the 1860s, but the Republicans of the 1980s did not broadly support it. Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign called for abolishing the DOE, stating, “Education is the principal responsibility of local school systems, teachers, parents, citizen boards, and state governments… It is not the business of the federal government (Reagan, 1981).” He framed his opposition around federal overreach, Tenth Amendment rights, and bureaucratic waste.

To date, conservation objections to the Department of Education are rooted in a strict interpretation of the Tenth Amendment, which states:

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

US Constitution, Amendment X.

Because the Constitution does not explicitly mention education, many conservatives—including President Ronald Reagan—argued that education policy should be handled exclusively by state and local governments. Reagan called the Department of Education an “unnecessary and intrusive layer of bureaucracy” and pledged during his 1980 campaign to eliminate it (Reagan, 1981). His administration’s position was that federal involvement infringed upon state sovereignty and undermined the constitutional balance of power. These concerns became a defining aspect of Republican education policy, reinforcing a deep ideological divide between those who advocate for decentralized local control and those who support a federal role in promoting equity and access to education.

However, the US Supreme Court has consistently upheld the federal government’s involvement in education when exercised through its spending power rather than direct mandates. In South Dakota v. Dole (1987), the Court affirmed that Congress may attach reasonable conditions to federal funds if those conditions are related to the federal interest. This decision undergirds many of the Department of Education’s programs, including Title I and IDEA, requiring states to meet specific criteria for funding. Additionally, in Board of Education v. Rowley (1982) and Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District (2017), the Court upheld the federal government’s role in guaranteeing the rights of students with disabilities under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Landmark civil rights decisions like Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and Lau v. Nichols (1974) also affirm the federal government’s duty to ensure equal access to education. These cases collectively illustrate that while education remains primarily a state responsibility, the federal government has a constitutionally valid role in advancing national educational interests, enforcing civil rights, and allocating conditional funding to support educational equity.

In other words, the DOE has a constitutional lane that limits its powers and protects states’ rights to set curricula and make decisions about licensure for teachers and administrators. The Department of Education is tasked with establishing policies, administering federal assistance, and enforcing educational laws related to privacy and civil rights.

So What Does All This Cost?

Since Reagan’s day, GOP platforms have consistently included language to reduce or eliminate the DOE’s role (Gewertz, 2024). Ironically, the Reagan Administration was responsible for halting efforts to dismantle the DOE when, in 1983, Reagan’s own National Commission released A Nation at Risk, warning of “a rising tide of mediocrity.” While the administration hoped to justify scaling back the DOE, the report galvanized public concern about education quality.

“If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war.”

(National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983)

The US ranked mediocre or declining in international comparisons of educational performance at the time. While PISA and TIMSS had not yet begun, studies showed US students falling behind in math and science compared to Japan, West Germany, and the Soviet Union (Gardner, 1983). Ravitch (2000) states, “A Nation at Risk gave the Department of Education something it had lacked before—a national sense of urgency and purpose.”

How Does the U.S. Stack Up Globally Today?

According to the PISA Scores (2018): We are 13th in reading, 18th in science, and 37th in Math: 37th out of 70 nations assessed (OECD, 2019). The US spends around $16,000 per student annually compared to the OECD average of ~$10,000. Despite relatively high spending, achievement gaps remain significant, especially along racial and socioeconomic lines.

Has the Department of Education Helped Address Educational Disparities?

It begs the question: if we are not leading the pack globally—and we are clearly not—has the Department of Education helped close the opportunity gaps here at home?

The answer is… complicated. But not nothing.

There are absolutely areas where the DOE has made a real difference. Title I funding supports schools in high-poverty areas, helping to bring in reading specialists, intervention programs, smaller class sizes, and more individualized support. IDEA ensures that students with disabilities are not left to fall through the cracks and that they receive the services and accommodations they need to succeed in public school settings. The Office for Civil Rights investigates and resolves thousands of discrimination complaints yearly—more than 10,000 in 2021 alone (US Department of Education, 2021). Additionally, programs like Pell Grants and TRIO have made college a dream and a real option for generations of low-income and first-generation students.

There is also strong evidence that this kind of investment works. Jackson, Johnson, and Persico (2016) found that increased education funding—when used effectively—can reduce long-term disparities in academic and life outcomes. In other words, money matters. Support matters. Furthermore, equity-focused federal investment can be a powerful tool for change.

However, even with all that, enormous challenges remain. Achievement gaps between racial and economic groups still exist, and in many places, they are getting worse. The way we fund schools—mainly through local property taxes—is wildly inequitable, a system the DOE does not control. Moreover, let us be honest: not every federal initiative has landed well. Efforts like No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top were met with mixed reviews. Some folks saw them as necessary nudges toward accountability and innovation; others (myself included) experienced them as top-down mandates that fueled anxiety narrowed the curriculum, and made teachers feel like test-prep robots.

The Department does not run schools, hand out grades, or write lesson plans. What it does do is offer support, protection, and guardrails—tools that help ensure some students are not consistently left behind just because of where they live, how they learn, or who they are.

So, the real question is not whether we should keep the DOE. It is this: How do we ensure it lives up to its promise?

Why We Must Defend the Department of Education

Proponents of the Department of Education argue that ensuring equal educational opportunities and upholding civil rights is essential. It plays a vital role in providing funding to support underserved schools, enforcing civil rights laws, and promoting policies that encourage educational equity. The Department’s mission is “to promote student achievement and preparation for global competitiveness by fostering educational excellence and ensuring equal access” (US Department of Education, n.d.).

Federal oversight helps address disparities in educational access and outcomes that states and local systems have often struggled—or refused—to correct on their own. The Department also promotes a more consistent national approach to educational quality, if still imperfect. Without it, the gaps between well-funded and under-resourced schools would likely widen, and civil rights protections for vulnerable students could be weakened or inconsistently applied.

Still, much of the resistance to the Department today stems not from budgetary concerns or a principled stance on federalism but from a deeper, more emotional place: fear. DEI, CRT, LGBTQ+ inclusion and even library books have become culture war proxies. This climate of outrage, often fueled by misinformation, is rooted in a zero-sum mindset—the idea that if one group gains something, another must lose. When people believe their children might fall behind in a so-called fairness war, they are more likely to support dismantling institutions they are told are the source of the threat.

But rejecting that kind of thinking opens the door to a more inclusive, sustainable vision for public education—one that fully justifies the existence of a strong Department of Education. When we see educational opportunity as something that grows through inclusion, not scarcity, we understand the Department not as a threat to local control but as a tool for national unity, fairness, and progress. As Heather McGhee (2021) reminds us, “When we pool our resources and work together across lines of difference, we can build something better for everyone” (p. 256).

Imaginary Monsters and Real Responsibilities

In the end, the Department of Education is not perfect. It does not run your child’s school, set curriculum, or force teachers to adopt a particular ideology. It funds programs that expand access for low-income students, protect the rights of children with disabilities, and enforce civil rights laws in education.

Nevertheless, facts often lose ground to fear in today’s political climate. DEI initiatives, CRT, LGBTQ+ inclusion, and book bans have become hot-button issues. They stir emotions and, more importantly, stir division. When people believe their children might “lose out” in a zero-sum game, they look for someone to blame. The DOE becomes the stand-in villain—the alligator under the bed. Some politicians are all too happy to play my dad’s role with a flashlight—stomping around and pretending to vanquish the danger. Unlike my dad, whose ultimate goal was to ensure that my sister understood there were no alligators or other monsters lurking under her bed, our leaders are altogether too content to fuel unwarranted fear for political gain.

This fear-based rhetoric is not just misguided—it is dangerous. It distracts from the real issues: unequal school funding, teacher shortages, crumbling infrastructure, and students slipping through the cracks. Instead of hunting imaginary monsters, we should focus on the shared goals of educational equity, opportunity, and national progress.

The DOE is not the enemy of public education—it is one of the only tools we have to ensure that it lives up to its promise. And just like my sister eventually outgrew her fear of alligators, maybe—just maybe—we can outgrow our fear of each other long enough to build a system that works better for everyone.

References

Barnard, H. (1868). Report of the Commissioner of Education. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/SERIALSET-01418_00_00-049-0190-0000/pdf/SERIALSET-01418_00_00-049-0190-0000.pdf

Board of Education of Hendrick Hudson Central School District v. Rowley, 458 U.S. 176 (1982).

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

Congressional Budget Office. (2023). The budget and economic outlook: 2023 to 2033. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58848

Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District RE-1, 580 U.S. 386 (2017).

Gardner, D. P. (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for educational reform. National Commission on Excellence in Education. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED226006

Jackson, C. K., Johnson, R. C., & Persico, C. (2016). The effects of school spending on educational and economic outcomes: Evidence from school finance reforms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(1), 157–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjv036

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974).

McGhee, H. (2021). The sum of us: What racism costs everyone and how we can prosper together. One World.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2019). PISA 2018 results. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/pisa-2018-results.htm

Reagan, R. (1981, July 30). Remarks at the annual convention of the National Conference of State Legislatures. The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-atlanta-georgia-the-annual-convention-the-national-conference-state-legislatures

South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203 (1987).

Thrush, G., & Edmondson, C. (2025, March 6). Trump and other Republicans want to abolish the Education Department. Can they? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/06/us/politics/trump-republicans-education-department.html

U.S. Const. amend. X.

U.S. Department of Education. (2021). Office for Civil Rights: Annual report to the Secretary, the President, and the Congress. https://www.ed.gov/about/ed-offices/ocr/serial-reports-regarding-ocr-activities

Leave a Reply